Introduction to turbulence/Turbulence kinetic energy

From CFD-Wiki

| Nature of turbulence |

| Statistical analysis |

| Reynolds averaged equation |

| Turbulence kinetic energy |

| Stationarity and homogeneity |

| Homogeneous turbulence |

| Free turbulent shear flows |

| Wall bounded turbulent flows |

| Study questions

... template not finished yet! |

Fluctuating kinetic energy

It is clear from the previous chapter that the straightforward application of ideas that worked well for viscous stresses do not work too well for turbulence Reynolds stresses. Moreover, even the attempt to directly derive equations for the Reynolds stresses using the Navier-Stokes equations as a starting point has left us with far more equations than unknowns. Unfortunately this means that the turbulence problem for engineers is not going to have a simple solution: we simply cannot produce a set of reasonably universal equations. Obviously we are going to have to study the turbulence fluctuations in more detail and learn how they get their energy (usually from the mean flow somehow), and what they ultimately do with it. Our hope is that by understanding more about turbulence itself, we will gain insight into how we might make closure approximations that will work, at least sometimes. Hopefully, we will also gain an understanding of when and why they will not work.

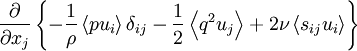

An equation for the fluctuating kinetic energy for constant density flow can be obtained directly from the Reynolds stress equation derived earlier, equation 3.35, by contracting the free indices. The result is:

|

| (1) |

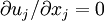

where the incompressibility condition (  ) has been used to eliminate the pressure-strain rate term, and

) has been used to eliminate the pressure-strain rate term, and  .

.

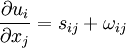

The last term can be simplified by recalling that the velocity deformation rate tensor,  , can be decomposed into symmetric and anti-symmetric parts; i.e.,

, can be decomposed into symmetric and anti-symmetric parts; i.e.,

|

| (2) |

where the symmetric part is the strain-rate tensor,  , and the anti-symmetric part is the rotation-rate tensor

, and the anti-symmetric part is the rotation-rate tensor  , defined by:

, defined by:

|

| (3) |

Since the double contraction of a symmetric tensor with an anti-symmetric tensor is identically zero, it follows immediately that:

|

| (4) |

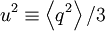

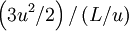

Now it is customary to define a new variable k, the average fluctuating kinetic energy per unit mass, by:

|

| (5) |

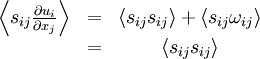

By dividing equation 1 by equation 2 and inserting this definition, the equation for the average kinetic energy per unit mass of the fluctuating motion can be re-written as:

|

| (6) |

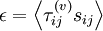

The role of each of these terms will be examined in detail later. First note that an alternative form of this equation can be derived by leaving the viscous stress in terms of the strain rate. We can obtain the appropriate form of the equation for the fluctuating momentum from equation 21 in origiins of turbulence by substituting the incompressible Newtonian constitutive equation into it to obtain:

|

| (7) |

If we take the scalar product of this with the fluctuating velocity itself and average, it follows (after some rearrangement) that:

|

| (8) |

Both equations 6 and 8 play an important role in the study of turbulence. The first form given by equation 6 will provide the framework for understanding the dynamics of turbulent motion. The second form, equation 8 forms the basis for most of the second-order closure attempts at turbulence modelling; e.g., the socalled k-e models ( usually referred to as the “k-epsilon models”). This because it has fewer unknowns to be modelled, although this comes at the expense of some extra assumptions about the last term. It is only the last term in equation 6 that can be identified as the true rate of dissipation of turbulence kinetic energy, unlike the last term in equation 8 which is only the dissipation when the flow is homogeneous. We will talk about homogeniety below, but suffice it to say now that it never occurs in nature. Nonetheless, many flows can be assumed to be homogeneous at the scales of turbulence which are important to this term, so-called local homogeniety.

Each term in the equation for the kinetic energy of the turbulence has a distinct role to play in the overall kinetic energy balance. Briefly these are:

- Rate of change of kinetic energy per unit mass due to non-stationarity; i.e., time dependence of the mean:

|

| (9) |

- Rate of change of kinetic energy per unit mass due to convection (or advection) by the mean flow through an inhomogenous field :

|

| (10) |

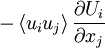

- Transport of kinetic energy in an inhomogeneous field due respectively to the pressure fluctuations, the turbulence itself, and the viscous stresses:

|

| (11) |

- Rate of production of turbulence kinetic energy from the mean flow(gradient):

|

| (12) |

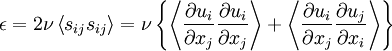

- Rate of dissipation of turbulence kinetic energy per unit mass due to viscous stresses:

|

| (12) |

These terms will be discussed in detail in the succeeding sections, and the role of each examined carefully.

Rate of dissipation of the turbulence kinetic energy

The last term in the equation for the kinetic energy of the turbulence has been identified as the rate of dissipation of the turbulence energy per unit mass; i.e.,

|

| (14) |

It is easy to see that  always, since it is a sum of the average of squared quantities only (i.e.

always, since it is a sum of the average of squared quantities only (i.e.  ). Also, since it occurs on the right hand side of the kinetic energy equation for the fluctuating motions preceded by a minus sign, it is clear that it can act only to reduce the kinetic energy of the flow. Therefore it causes a negative rate of change of kinetic energy; hence the name dissipation.

). Also, since it occurs on the right hand side of the kinetic energy equation for the fluctuating motions preceded by a minus sign, it is clear that it can act only to reduce the kinetic energy of the flow. Therefore it causes a negative rate of change of kinetic energy; hence the name dissipation.

Physically, enegry is dissipated because of the work done by the fluctuating viscous stresses in resisting deformation of the fluid material by the fluctuating strain rates; i.e.

|

| (15) |

This reduces to equation 14 only for a Newtonian fluid. In non-Newtonian fluids, protions of this product may not be negative implying that it may not all represent an irrecoverable loss of fluctuating kinetic energy.

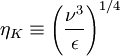

It will be shown in the following chapter on Stationarity and homogenity that the dissipation of turbulence energy mostly takes place at the smallest turbulence scales, and that those scales can be characterized by so-called Kolmogorov microscale defined by:

|

| (16) |

In atmospheric motions where the length scale for those eddies having the most turbulence energy (and responsible for the Reynolds stress) can be measured in kilometers, typical values of the Kolmogorov microscale range from 0.1 - 10 millimeters. In laboratory flows where the overall scale of the flow is greatly reduced, much smaller values of  are not uncommon. The small size of these dissipative scales greately complicates measurement of energy balances, since the largest measuring dimension must be about equal to twice the Kolmogorov microscale. And it is the range of scales,

are not uncommon. The small size of these dissipative scales greately complicates measurement of energy balances, since the largest measuring dimension must be about equal to twice the Kolmogorov microscale. And it is the range of scales,  , which makes direct numerical simulation of most interesting flows impossible, since the required number of computational cells is several orders of magnitude greater that

, which makes direct numerical simulation of most interesting flows impossible, since the required number of computational cells is several orders of magnitude greater that  . This same limitation also affects experiments as well, which must often be quite large to be useful.

. This same limitation also affects experiments as well, which must often be quite large to be useful.

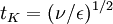

One of the consequences of this great separation of scales between those containing the bulk of the turbulence energy and those dissipating it is that the dissipation rate is primarily determined by the large scales and not the small. This is because the viscous scales (which operate on a time scale of  ) dissipate rapidly any energy sent down to them by non-linear processes of scale to scale energy transfer. Thus the overall rate of dissipation is controlled by the rate of energy transfer from the energetic scales, primarily by the non-linear scale-to-scale transfer. This will be discussed later when we consider the energy spactrum. But for now it is important only note that a consequence of this is that the dissipation rate is given approximately as:

) dissipate rapidly any energy sent down to them by non-linear processes of scale to scale energy transfer. Thus the overall rate of dissipation is controlled by the rate of energy transfer from the energetic scales, primarily by the non-linear scale-to-scale transfer. This will be discussed later when we consider the energy spactrum. But for now it is important only note that a consequence of this is that the dissipation rate is given approximately as:

|

| (17) |

where  and

and  is an integral length scale. It is easy to remember this relation if you note that the time scale of the energetic turbulent eddies can be estimated as

is an integral length scale. It is easy to remember this relation if you note that the time scale of the energetic turbulent eddies can be estimated as  . Thus

. Thus  can estimated as

can estimated as  .

.

Sometimes it is convenient to just define the "length scale of the energy containing eddies" (or the pseudo-integral scale) as:

|

| (18) |

Almost always  , but the relation is at most only exact theoretically in the limit of infinite Reynolds number since the constant of proportionality is Reynolds number dependent. The Reynolds number dependence of the ratio

, but the relation is at most only exact theoretically in the limit of infinite Reynolds number since the constant of proportionality is Reynolds number dependent. The Reynolds number dependence of the ratio  for grid turbulence is illustrated in Figure 4.1. Many interpret this data to suggest that this ratioapproaches a constant and ignore the scatter. In fact some assume ratio to be constant and even refer to

for grid turbulence is illustrated in Figure 4.1. Many interpret this data to suggest that this ratioapproaches a constant and ignore the scatter. In fact some assume ratio to be constant and even refer to  though it were the real integral scale. Others

argue that the scatter is because of the differing upstream conditions and that the ratio may not be constant at all. It is really hard to tell who is right in the absence of facilities or simulations in which the Reynolds number can vary very much for fixed initial conditions. This all may leave you feeling a bit confused, but that’s the way turbulence is right now. It’s a lot easier to teach if we just tell you one view, but that’s not very good preparation for the future.

though it were the real integral scale. Others

argue that the scatter is because of the differing upstream conditions and that the ratio may not be constant at all. It is really hard to tell who is right in the absence of facilities or simulations in which the Reynolds number can vary very much for fixed initial conditions. This all may leave you feeling a bit confused, but that’s the way turbulence is right now. It’s a lot easier to teach if we just tell you one view, but that’s not very good preparation for the future.

Credits

This text was based on "Lectures in Turbulence for the 21st Century" by Professor William K. George, Professor of Turbulence, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

![\begin{matrix}

\left[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \left\langle u_{i} u_{i} \right\rangle + U_{j} \frac{\partial }{\partial x_{j} } \left\langle u_{i} u_{i} \right\rangle \right] \\

& = & \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}} \left\{ -\frac{2}{\rho} \left\langle p u_{i} \right\rangle \delta_{ij} - \left\langle q^{2} u_{j} \right\rangle + 4 \nu \left\langle s_{ij} u_{i} \right\rangle \right\} \\

& & - 2 \left\langle u_{i}u_{j} \right\rangle \frac{\partial U_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} - 4 \nu \left\langle s_{ij} \frac{\partial u_{i}}{\partial x_{j} } \right\rangle \\

\end{matrix}](/W/images/math/c/d/d/cdd713e7c866ab3a41c1db5df222a7b2.png)

![\omega_{ij} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \frac{\partial u_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} - \frac{\partial u_{j}}{\partial x_{i}} \right]](/W/images/math/b/7/7/b771bd4a8422189e342acf06c33672da.png)

![k \equiv \frac{1}{2} \left\langle u_{i}u_{i} \right\rangle = \frac{1}{2} \left\langle q^{2} \right\rangle = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \left\langle u^{2}_{1} \right\rangle + \left\langle u^{2}_{2} \right\rangle + \left\langle u^{2}_{3} \right\rangle \right]](/W/images/math/5/f/4/5f49df0b6717a9a52c142a281cda814f.png)

![\begin{matrix}

\left[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + U_{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}} \right] k & = & \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}} \left\{ - \frac{1}{\rho} \left\langle pu_{i} \right\rangle \delta_{ij} - \frac{1}{2} \left\langle q^{2} u_{j} \right\rangle + 2 \nu \left\langle s_{ij}u_{i} \right\rangle \right\} \\

& & - \left\langle u_{i}u_{j} \right\rangle \frac{\partial U_{i}}{\partial x_{j} } - 2 \nu \left\langle s_{ij} s_{ij} \right\rangle \\

\end{matrix}](/W/images/math/d/3/e/d3e5c43dd0769a3aad2fa9455ba955af.png)

![\left[ \frac{\partial }{\partial t } + U_{j} \frac{\partial }{\partial x_{j} } \right] u_{i} = - \frac{1}{\rho} \frac{\partial p}{\partial x_{i}} + \nu \frac{\partial^{2} u_{i}}{ \partial x^{2}_{j}} - \left[ u_{j} \frac{\partial U_{i}}{\partial x_{j} } \right] - \left\{ u_{j} \frac{\partial u_{i}}{ \partial x_{j}} - \left\langle u_{j} \frac{\partial u_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} \right\rangle \right\}](/W/images/math/e/0/b/e0b4576b17fa45fb1c66a20067c611f4.png)

![\begin{matrix}

\left[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + U_{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j}} \right] k & = & \frac{\partial }{ \partial x_{j} } \left\{ - \frac{1}{\rho} \left\langle pu_{i} \right\rangle \delta_{ij} - \frac{1}{2} \left\langle q^{2} u_{j} \right\rangle + \nu \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{j} } k \right\} \\

& & - \left\langle u_{i} u_{j} \right\rangle \frac{\partial U_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} - \nu \left\langle \frac{\partial u_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} \frac{\partial u_{i}}{\partial x_{j}} \right\rangle\\

\end{matrix}](/W/images/math/5/b/7/5b7fd5594272d4c5ca943c732ada6978.png)