Introduction to turbulence/Wall bounded turbulent flows

From CFD-Wiki

(→Introduction) |

(→The "outer" turbulent boundary layer) |

||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

surface using Euler’s equation. Then use the pressure along the surface from this ''inviscid'' solution together with the boundary layer equation to calculate the boundary layer flow. If you wish, you can even use an iterative procedure where you recalculate the outside flow over a streamline which was been displaced from the body by the boundary layer displacement thickness, and then re-calculate the boundary layer, etc. Before modern computers, this was the only way to calculate the flow around an airfoil, for example. | surface using Euler’s equation. Then use the pressure along the surface from this ''inviscid'' solution together with the boundary layer equation to calculate the boundary layer flow. If you wish, you can even use an iterative procedure where you recalculate the outside flow over a streamline which was been displaced from the body by the boundary layer displacement thickness, and then re-calculate the boundary layer, etc. Before modern computers, this was the only way to calculate the flow around an airfoil, for example. | ||

| - | + | == The "outer" turbulent boundary layer == | |

Revision as of 16:35, 25 August 2011

Introduction

Without the presence of walls or surfaces, turbulence in the absence of density fluctuations could not exist. This is because it is only at surfaces that vorticity can actually be generated by an on-coming flow is suddenly brought to rest to satisfy the no-slip condition. The vorticity generated at the leading edge can then be diffused, transported and amplified. But it can only be generated at the wall, and then only at the leading edge at that. Once the vorticity has been generated, some flows go on to develop in the absence of walls, like the free shear flows we considered earlier. Other flows remained “attached” to the surface and evolve entirely under the influence of it. These are generally referred to as “wall-bounded flows” or “boundary layer flows”. The most obvious causes for the effects of the wall on the flow arise from the wall-boundary conditions. In particular,

- The kinematic boundary condition demands that the normal velocity of

the fluid on the surface be equal to the normal velocity of the surface. This means there can be no-flow through the surface. Since the velocity normal to the surface cannot just suddenly vanish, the kinematic boundary condition ensures that the normal velocity components in wall-bounded flows are usually much less than in free shear flows. Thus the presence of the wall reduces the entrainment rate. Note that viscosity is not necessary in the equations to satisfy this condition, and it can be met even by solutions to to the inviscid Euler’s equations.

- The no-slip boundary condition demands that the velocity component tangential to the wall be the same as the tangential velocity of the wall. If the

wall is at rest relative, then the no-slip condition demands the tangential flow velocity be identically zero at the surface.

Figure 8.1: Flow around a simple airfoil without separation.

It is the no-slip condition, of course, that led Ludwig Prandtl1 to the whole

idea of a boundary layer in the first place. Professor Prandt literally saved fluid mechanics from d’Alembert’s paradox: the fact that there seemed to be no drag in an inviscid fluid (not counting form drag). Prior to Prandtl, everyone thought that as the Reynolds number increased, the flow should behave more and more like an inviscid fluid. But when there were surfaces, it clearly didn’t. Instead of behaving like those nice potential flow solutions (like around cylinders, for example), the flow not only produced drag, but often separated and produced wakes and other free shear flows. Clearly something was very wrong, and as a result fluid mechanics didn’t get much respect from engineers in the 19th century.

And with good reason: how useful could a bunch of equations be if they couldn’t

find viscous drag, much less predict how much. But Prandtl’s idea of the boundary

layer saved everything.

Prandtl’s great idea was the recognition that the viscous no-slip condition could not be met without somehow retaining at least one viscous stress term in the equations. As we shall see below, this implies that there must be at least two length scales in the flow, unlike the free shear flows we considered in the previous chapter for which the mean flow could be characterized by only a single length scale. The second length scale characterizes changes normal to the wall, and make it clear precisely which viscous term in the instantaneous equations is important.

Review of laminar boundary layers

Let’s work this all out for ourselves by considering what happens if we try to

apply the kinematic and no-slip boundary conditions to obtain solutions of the

Navier-Stokes equations in the infinite Reynolds number limit. Let’s restrict our

attention for the moment to the laminar flow of a uniform stream of speed,  ,

around a body of characteristic dimension, D, as shown in Figure 8.1. It is easy

to see the problem if we non-dimensionalize our equations using the free stream

boundary condition and body dimension. The result is:

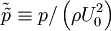

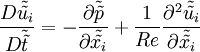

,

around a body of characteristic dimension, D, as shown in Figure 8.1. It is easy

to see the problem if we non-dimensionalize our equations using the free stream

boundary condition and body dimension. The result is:

|

| (1) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . The kinematic viscosity,

. The kinematic viscosity,  has disappeared entirely, and is included in the Reynolds number defined by:

has disappeared entirely, and is included in the Reynolds number defined by:

|

| (2) |

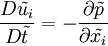

Now consider what happens as the Reynolds number increases, due to the increase of  or

or  , or even a decrease in the viscosity. Obviously the viscous terms become relatively less important. In fact, if the Reynolds number is large enough it is hard to see at first glance why any viscous term should be retained at all. Certainly in the limit as

, or even a decrease in the viscosity. Obviously the viscous terms become relatively less important. In fact, if the Reynolds number is large enough it is hard to see at first glance why any viscous term should be retained at all. Certainly in the limit as  , our equations must reduce to Euler’s equations which have no viscous terms at all; i.e., in dimensionless form,

, our equations must reduce to Euler’s equations which have no viscous terms at all; i.e., in dimensionless form,

|

| (3) |

Now if we replace the Navier-Stokes equations by Euler’s equations, this presents no problem at all in satisfying the kinematic boundary condition on the body’s surface. We simply solve for the inviscid flow by replacing the boundary of the body by a streamline. This automatically satisfies the kinematic boundary condition. If the flow can be assumed irrotational, then the problem reduces to a solution of Laplace’s equation, and powerful potential flow methods can be used.

In fact, for potential flow, it is possible to show that the flow is entirely determined by the normal velocity at the surface. And this is, of course, the source of our problem. There is no role left for the viscous no-slip boundary condition. And indeed, the potential flow has a tangential velocity along the surface streamline that is not zero. The problem, of course, is the absence of viscous terms in the Euler equations we used. Without viscous stresses acting near the wall to retard the flow, the solution cannot adjust itself to zero velocity at the wall. But how can viscosity enter the equations when our order-of-magnitude analysis says they are negligible at large Reynolds number, and exactly zero in the infinite Reynolds number limit. At the end of the nineteenth century, this was arguably the most serious problem confronting fluid mechanics.

Prandtl was the first to realize that there must be at least one viscous term

in the problem to satisfy the no-slip condition. Therefore he postulated that the

strain rate very near the surface would become as large as necessary to compensate for the vanishing effect of viscosity, so that at least one viscous term remained. This very thin region near the wall became known as Prandtl’s boundary layer, and the length scale characterizing the necessary gradient in velocity became known as the boundary layer “thickness”.

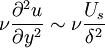

Prandtl’s argument for a laminar boundary layer can be quickly summarized using the same kind of order-of-magnitude analysis we used in Chapter 7 (here necessary make navigation !!!). For the leading viscous term:

|

| (4) |

where  is the new length scale characterizing changes normal to the plate near the wall and we have assumed

is the new length scale characterizing changes normal to the plate near the wall and we have assumed  . In fact, for a boundary layer next to walls driven by an external stream speed

. In fact, for a boundary layer next to walls driven by an external stream speed  . For the leading convection term:

. For the leading convection term:

|

| (5) |

The viscous term can survive only if it is the same order of magnitude as the convection term. Hence it follows that we must have:

|

| (6) |

This in turn requires that new length scale  must satisfy:

must satisfy:

|

| (7) |

or

|

| (8) |

Thus, for a laminar flow  grows like

grows like  . Now if you go back to your fluid mechanics texts and look at the similarity solution for a Blasius boundary layer, you will see this is exactly right if you take

. Now if you go back to your fluid mechanics texts and look at the similarity solution for a Blasius boundary layer, you will see this is exactly right if you take  , which is what we might have guessed anyway.

, which is what we might have guessed anyway.

It is very important to remember that the momentum equation is a vector equation, and we therefore have to scale all components of this vector equation the same way to preserve its direction. Therefore we must carry out the same kind of estimates for the cross-stream momentum equations as well. For a laminar boundary layer this can be easily be shown to reduce to:

|

| (9) |

Note that a only single term survives in the limit as the Reynolds number goes to

infinity, the cross-stream pressure gradient. Hence, for very large Reynolds number, the pressure gradient across the boundary layer equation is very small. Thus the pressure in the boundary is imposed on it by the flow outside the boundary layer. And this flow outside the boundary layer is governed to first order by Euler’s equation.

The fact that the pressure is imposed on the boundary layer provides us an

easy way to calculate such a flow. First calculate the inviscid flow along the

surface using Euler’s equation. Then use the pressure along the surface from this inviscid solution together with the boundary layer equation to calculate the boundary layer flow. If you wish, you can even use an iterative procedure where you recalculate the outside flow over a streamline which was been displaced from the body by the boundary layer displacement thickness, and then re-calculate the boundary layer, etc. Before modern computers, this was the only way to calculate the flow around an airfoil, for example.

![\delta \sim \left[ \frac{\nu L}{U_{s}} \right]^{1/2}](/W/images/math/d/c/d/dcd40e1c6fe0b947b08a89273c8922a6.png)

![\frac{\delta}{L} \sim \left[ \frac{\nu }{U_{s} L} \right]^{1/2}](/W/images/math/5/1/0/5109f2a3964f3b5997eeeee387ad7f8c.png)

![\left[ \frac{\delta}{L} \right] \left\{ \frac{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{ u}}}{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{t}}} + \tilde{\tilde{u}} \frac{\partial \tilde{\tilde{ u}} }{\tilde{\tilde{ x}}}+ \tilde{\tilde{v}} \frac{\partial \tilde{\tilde{ v}} }{\tilde{\tilde{ y}}} \right\} = - \frac{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{p}}_{\infty}}{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{ y}} } + \frac{1}{Re} \left[ \frac{\delta}{L} \right] \left\{ \frac{ \partial^{2} \tilde{\tilde{v}} }{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{ y}}^{2}} \right\} + \frac{1}{Re} \left\{ \frac{ \partial^{2} \tilde{\tilde{v}} }{ \partial \tilde{\tilde{ x}}^{2}} \right\}](/W/images/math/1/d/8/1d809934e9ae0d115665576eb95a0b1c.png)