Introduction to turbulence/Statistical analysis/Ensemble average

From CFD-Wiki

(→Fluctuations about the mean) |

m (→Fluctuations about the mean) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | + | {{Introduction to turbulence menu}} | |

| - | + | ||

== The mean or ensemble average == | == The mean or ensemble average == | ||

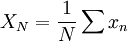

| - | The concept of an '' | + | The concept of an ''ensemble average'' is based upon the existence of independent statistical event. For example, consider a number of inviduals who are simultaneously flipping unbiased coins. If a value of one is assigned to a head and the value of zero to a tail, then the ''arithmetic average'' of the numbers generated is defined as |

| - | + | :<math>X_{N}=\frac{1}{N} \sum{x_{n}}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

where our <math> n </math> th flip is denoted as <math> x_{n} </math> and <math> N </math> is the total number of flips. | where our <math> n </math> th flip is denoted as <math> x_{n} </math> and <math> N </math> is the total number of flips. | ||

| + | Now if all the coins are the same, it doesn't really matter whether we flip one coin <math> N </math> times, or <math> N </math> coins a single time. The key is that they must all be ''independent events'' - meaning the probability of achieving a head or tail in a given flip must be completely independent of what happens in all the other flips. Obviously we can't just flip one coin and count it <math> N </math> times; these cleary would not be independent events | ||

| - | + | '''Exercise:''' Carry out an experiment where you flip a coin 100 times in groups of 10 flips each. Compare the values you get for <math>X_{10}</math> for each of the 10 groups, and note how they differ from the value of <math>X_{100}</math>. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

Unless you had a very unusual experimental result, you probably noticed that the value of the <math> X_{10} </math>'s was also a random variable and differed from ensemble to ensemble. Also the greater the number of flips in the ensemle, the closer you got to <math>X_{N}=1/2 </math>. Obviously the bigger <math> N </math> , the less fluctuation there is in <math> X_{N} </math> | Unless you had a very unusual experimental result, you probably noticed that the value of the <math> X_{10} </math>'s was also a random variable and differed from ensemble to ensemble. Also the greater the number of flips in the ensemle, the closer you got to <math>X_{N}=1/2 </math>. Obviously the bigger <math> N </math> , the less fluctuation there is in <math> X_{N} </math> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 16: | ||

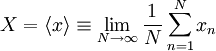

Now imagine that we are trying to establish the nature of a random variable <math> x </math>. The <math>n</math>th ''realization'' of <math> x </math> is denoted as <math> x_{n}</math>. The ''ensemble average'' of <math> x </math> is denoted as <math> X </math> (or <math> \left\langle x \right\rangle </math> ), and ''is defined as'' | Now imagine that we are trying to establish the nature of a random variable <math> x </math>. The <math>n</math>th ''realization'' of <math> x </math> is denoted as <math> x_{n}</math>. The ''ensemble average'' of <math> x </math> is denoted as <math> X </math> (or <math> \left\langle x \right\rangle </math> ), and ''is defined as'' | ||

| - | + | :<math>X = \left\langle x \right\rangle \equiv \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} x_{n}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | X = \left\langle x \right\rangle \equiv \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} x_{n} | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

Obviously it is impossible to obtain the ensemble average experimentally, since we can never achieve an infinite number of independent realizations. The most we can ever obtain is the arithmetic mean for the number of realizations we have. For this reason the arithmetic mean can also referred to as the ''estimator'' for the true mean ensemble average. | Obviously it is impossible to obtain the ensemble average experimentally, since we can never achieve an infinite number of independent realizations. The most we can ever obtain is the arithmetic mean for the number of realizations we have. For this reason the arithmetic mean can also referred to as the ''estimator'' for the true mean ensemble average. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 22: | ||

Even though the true mean (or ensemble average) is unobtainable, nonetheless, the idea is still very useful. Most importantly,we can almost always be sure the ensemble average exists, even if we can only estimate what it really is. The fact of its existence, however, does not always mean that it is easy to obtain in practice. All the theoretical deductions in this course will use this ensemble average. Obviously this will mean we have to account for these "statistical differenced" between true means and estimates when comparing our theoretical results to actual measurements or computations. | Even though the true mean (or ensemble average) is unobtainable, nonetheless, the idea is still very useful. Most importantly,we can almost always be sure the ensemble average exists, even if we can only estimate what it really is. The fact of its existence, however, does not always mean that it is easy to obtain in practice. All the theoretical deductions in this course will use this ensemble average. Obviously this will mean we have to account for these "statistical differenced" between true means and estimates when comparing our theoretical results to actual measurements or computations. | ||

| - | + | <font color="orange" size=3>Figure 2.1 not uploaded yet</font> | |

| - | + | In general, the <math> x_{n}</math> could be realizations of any random variable. The <math> X </math> defined by the ensemle average definition defined above represents the ensemble average of it. The quantity <math> X </math> is sometimes referred to as the ''expected value '' of the random variables <math> x </math> , or even simple its ''mean''. | |

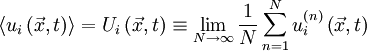

| - | < | + | For example, the velocity vector at a given point in space and time <math>\vec{x},t </math> , in a given turbulent flow can be considered to be a random variable, say <math> u_{i} \left( \vec{x},t \right) </math>. If there were a large number of identical experiments so that the <math> u^{\left( n \right)}_{i} \left( \vec{x},t \right) </math> in each of them were identically distributed, then the ensemble average of <math> u^{\left( n \right)}_{i} \left( \vec{x},t \right) </math> would be given by |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | < | + | :<math>\left\langle u_{i} \left( \vec{x} , t \right) \right\rangle = U_{i} \left( \vec{x} , t \right) \equiv \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} u^{ \left( n \right) }_{i} \left( \vec{x} , t \right)</math> |

| - | + | ||

| - | Note that this ensemble average, <math> U_{i} \left( | + | Note that this ensemble average, <math> U_{i} \left( \vec{x},t \right) </math> , will, in general, vary with independent variables <math>\vec{x}</math> and <math>t</math>. It will be seen later, that under certain conditions the ensemble average is the same as the average which would be generated by averaging in time. Even when a time average is not meaningful, however, the ensemble average can still be defined; e.g., as in non-stationary or periodic flow. Only ensemble averages will be used in the development of the turbulence equations here unless otherwise stated. |

== Fluctuations about the mean == | == Fluctuations about the mean == | ||

| Line 51: | Line 36: | ||

It is often important to know how a random variable is distributed about the mean. For example, figure 2.1 illustrates portions of two random functions of time which have identical means, but are obviously members of different ensembles since the amplitudes of their fluctuations are not distributed the same. it is possible to distinguish between them by examining the statistical properties of the fluctuations about the mean (or simply the fluctuations) defined by: | It is often important to know how a random variable is distributed about the mean. For example, figure 2.1 illustrates portions of two random functions of time which have identical means, but are obviously members of different ensembles since the amplitudes of their fluctuations are not distributed the same. it is possible to distinguish between them by examining the statistical properties of the fluctuations about the mean (or simply the fluctuations) defined by: | ||

| - | + | :<math>x' = x - X</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

It is easy to see that the average of the fluctuation is zero, i.e., | It is easy to see that the average of the fluctuation is zero, i.e., | ||

| - | + | :<math>\left\langle x' \right\rangle = 0</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | On the other hand, the ensemble average of the square of the fluctuation is ''not'' zero. In fact, it is such an important statistical measure we give it a special name, the '''variance''', and represent it symbolically by either <math> var \left[ x \right] </math> or <math> \left\langle \left( x | + | On the other hand, the ensemble average of the square of the fluctuation is ''not'' zero. In fact, it is such an important statistical measure we give it a special name, the '''variance''', and represent it symbolically by either <math> var \left[ x \right] </math> or <math> \left\langle \left( x' \right) ^{2} \right\rangle </math> |

The ''variance'' is defined as | The ''variance'' is defined as | ||

| - | + | :<math>var \left[ x \right] \equiv \left\langle \left( x' \right) ^{2} \right\rangle = \left\langle \left[ x - X \right]^{2} \right\rangle</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | var \left[ x \right] \equiv \left\langle \left( x | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | :<math>= \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} \left[ x_{n} - X \right]^{2}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | = \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} \left[ x_{n} - X \right]^{2} | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

Note that the variance, like the ensemble average itself, can never really be measured, since it would require an infinite number of members of the ensemble. | Note that the variance, like the ensemble average itself, can never really be measured, since it would require an infinite number of members of the ensemble. | ||

| + | It is straightforward to show from the definition of ensemble average the variance can be written as | ||

| - | + | :<math>var \left[ x \right] = \left\langle x^{2} \right\rangle - X^{2}</math> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | var \left[ x \right] = \left\langle x^{2} \right\rangle - X^{2} | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

Thus the variance is the ''second-moment'' minus the square of the ''first-moment'' (or mean). In this naming convention, the ensemble mean is the ''first moment''. | Thus the variance is the ''second-moment'' minus the square of the ''first-moment'' (or mean). In this naming convention, the ensemble mean is the ''first moment''. | ||

| - | |||

The variance can also referred to as the ''second central moment of x''. The word central implies that the mean has been subtracted off before squaring and averaging. The reasons for this will be clear below. If two random variables are identically distributed, then they must have the same mean and variance. | The variance can also referred to as the ''second central moment of x''. The word central implies that the mean has been subtracted off before squaring and averaging. The reasons for this will be clear below. If two random variables are identically distributed, then they must have the same mean and variance. | ||

| Line 98: | Line 61: | ||

The variance is closely related to another statistical quantity called the ''standard deviation'' or root mean square (''rms'') value of the random variable <math> x </math> , which is denoted by the symbol, <math> \sigma_{x} </math>. Thus, | The variance is closely related to another statistical quantity called the ''standard deviation'' or root mean square (''rms'') value of the random variable <math> x </math> , which is denoted by the symbol, <math> \sigma_{x} </math>. Thus, | ||

| - | + | :<math>\sigma_{x} \equiv \left( var \left[ x \right] \right)^{1/2}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | \sigma_{x} \equiv \left( var \left[ x \right] \right)^{1/2} | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

or | or | ||

| - | + | :<math>\sigma^{2}_{x} = var \left[ x \right]</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | \sigma^{2}_{x} = var \left[ x \right] | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | <font color="orange" size=3>Figure 2.2 not uploaded yet</font> | |

== Higher moments == | == Higher moments == | ||

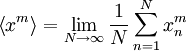

| - | Figure 2.2 illustrates | + | Figure 2.2 illustrates two random variables of time which have the same mean and also the same variances, but clearly they are still quite different. It is useful, therefore, to define higher moments of the distribution to assist in distinguishing these differences. |

| - | The <math> m </math>-th moment of the random variable is defined as | + | The <math>m</math>-th moment of the random variable is defined as |

| - | + | :<math>\left\langle x^{m} \right\rangle = \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} x^{m}_{n}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | \left\langle x^{m} \right\rangle = \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} x^{m}_{n} | + | |

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

It is usually more convenient to work with the ''central moments'' defined by: | It is usually more convenient to work with the ''central moments'' defined by: | ||

| - | + | :<math>\left\langle \left( x' \right)^{m} \right\rangle = \left\langle \left( x-X \right)^{m} \right\rangle = \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} \left[x_{n} - X \right]^{m}</math> | |

| - | :<math> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </math | + | |

| - | + | ||

The central moments give direct information on the distribution of the values of the random variable about the mean. It is easy to see that the variance is the second central moment (i.e., <math> m=2 </math> ). | The central moments give direct information on the distribution of the values of the random variable about the mean. It is easy to see that the variance is the second central moment (i.e., <math> m=2 </math> ). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Turbulence credit wkgeorge}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Chapter navigation||Probability}} | ||

Latest revision as of 12:29, 2 July 2011

Contents |

The mean or ensemble average

The concept of an ensemble average is based upon the existence of independent statistical event. For example, consider a number of inviduals who are simultaneously flipping unbiased coins. If a value of one is assigned to a head and the value of zero to a tail, then the arithmetic average of the numbers generated is defined as

where our  th flip is denoted as

th flip is denoted as  and

and  is the total number of flips.

is the total number of flips.

Now if all the coins are the same, it doesn't really matter whether we flip one coin  times, or

times, or  coins a single time. The key is that they must all be independent events - meaning the probability of achieving a head or tail in a given flip must be completely independent of what happens in all the other flips. Obviously we can't just flip one coin and count it

coins a single time. The key is that they must all be independent events - meaning the probability of achieving a head or tail in a given flip must be completely independent of what happens in all the other flips. Obviously we can't just flip one coin and count it  times; these cleary would not be independent events

times; these cleary would not be independent events

Exercise: Carry out an experiment where you flip a coin 100 times in groups of 10 flips each. Compare the values you get for  for each of the 10 groups, and note how they differ from the value of

for each of the 10 groups, and note how they differ from the value of  .

.

Unless you had a very unusual experimental result, you probably noticed that the value of the  's was also a random variable and differed from ensemble to ensemble. Also the greater the number of flips in the ensemle, the closer you got to

's was also a random variable and differed from ensemble to ensemble. Also the greater the number of flips in the ensemle, the closer you got to  . Obviously the bigger

. Obviously the bigger  , the less fluctuation there is in

, the less fluctuation there is in

Now imagine that we are trying to establish the nature of a random variable  . The

. The  th realization of

th realization of  is denoted as

is denoted as  . The ensemble average of

. The ensemble average of  is denoted as

is denoted as  (or

(or  ), and is defined as

), and is defined as

Obviously it is impossible to obtain the ensemble average experimentally, since we can never achieve an infinite number of independent realizations. The most we can ever obtain is the arithmetic mean for the number of realizations we have. For this reason the arithmetic mean can also referred to as the estimator for the true mean ensemble average.

Even though the true mean (or ensemble average) is unobtainable, nonetheless, the idea is still very useful. Most importantly,we can almost always be sure the ensemble average exists, even if we can only estimate what it really is. The fact of its existence, however, does not always mean that it is easy to obtain in practice. All the theoretical deductions in this course will use this ensemble average. Obviously this will mean we have to account for these "statistical differenced" between true means and estimates when comparing our theoretical results to actual measurements or computations.

Figure 2.1 not uploaded yet

In general, the  could be realizations of any random variable. The

could be realizations of any random variable. The  defined by the ensemle average definition defined above represents the ensemble average of it. The quantity

defined by the ensemle average definition defined above represents the ensemble average of it. The quantity  is sometimes referred to as the expected value of the random variables

is sometimes referred to as the expected value of the random variables  , or even simple its mean.

, or even simple its mean.

For example, the velocity vector at a given point in space and time  , in a given turbulent flow can be considered to be a random variable, say

, in a given turbulent flow can be considered to be a random variable, say  . If there were a large number of identical experiments so that the

. If there were a large number of identical experiments so that the  in each of them were identically distributed, then the ensemble average of

in each of them were identically distributed, then the ensemble average of  would be given by

would be given by

Note that this ensemble average,  , will, in general, vary with independent variables

, will, in general, vary with independent variables  and

and  . It will be seen later, that under certain conditions the ensemble average is the same as the average which would be generated by averaging in time. Even when a time average is not meaningful, however, the ensemble average can still be defined; e.g., as in non-stationary or periodic flow. Only ensemble averages will be used in the development of the turbulence equations here unless otherwise stated.

. It will be seen later, that under certain conditions the ensemble average is the same as the average which would be generated by averaging in time. Even when a time average is not meaningful, however, the ensemble average can still be defined; e.g., as in non-stationary or periodic flow. Only ensemble averages will be used in the development of the turbulence equations here unless otherwise stated.

Fluctuations about the mean

It is often important to know how a random variable is distributed about the mean. For example, figure 2.1 illustrates portions of two random functions of time which have identical means, but are obviously members of different ensembles since the amplitudes of their fluctuations are not distributed the same. it is possible to distinguish between them by examining the statistical properties of the fluctuations about the mean (or simply the fluctuations) defined by:

It is easy to see that the average of the fluctuation is zero, i.e.,

On the other hand, the ensemble average of the square of the fluctuation is not zero. In fact, it is such an important statistical measure we give it a special name, the variance, and represent it symbolically by either ![var \left[ x \right]](/W/images/math/d/1/c/d1c43f684f5952bdd96132dfa2ada32a.png) or

or  The variance is defined as

The variance is defined as

Note that the variance, like the ensemble average itself, can never really be measured, since it would require an infinite number of members of the ensemble.

It is straightforward to show from the definition of ensemble average the variance can be written as

Thus the variance is the second-moment minus the square of the first-moment (or mean). In this naming convention, the ensemble mean is the first moment.

The variance can also referred to as the second central moment of x. The word central implies that the mean has been subtracted off before squaring and averaging. The reasons for this will be clear below. If two random variables are identically distributed, then they must have the same mean and variance.

The variance is closely related to another statistical quantity called the standard deviation or root mean square (rms) value of the random variable  , which is denoted by the symbol,

, which is denoted by the symbol,  . Thus,

. Thus,

or

Figure 2.2 not uploaded yet

Higher moments

Figure 2.2 illustrates two random variables of time which have the same mean and also the same variances, but clearly they are still quite different. It is useful, therefore, to define higher moments of the distribution to assist in distinguishing these differences.

The  -th moment of the random variable is defined as

-th moment of the random variable is defined as

It is usually more convenient to work with the central moments defined by:

The central moments give direct information on the distribution of the values of the random variable about the mean. It is easy to see that the variance is the second central moment (i.e.,  ).

).

Credits

This text was based on "Lectures in Turbulence for the 21st Century" by Professor William K. George, Professor of Turbulence, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

![var \left[ x \right] \equiv \left\langle \left( x' \right) ^{2} \right\rangle = \left\langle \left[ x - X \right]^{2} \right\rangle](/W/images/math/d/7/4/d74ae1437b60cb928198931c8e240985.png)

![= \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} \left[ x_{n} - X \right]^{2}](/W/images/math/3/b/d/3bd51fe3a21e39adbfe74ee96de9f7b0.png)

![var \left[ x \right] = \left\langle x^{2} \right\rangle - X^{2}](/W/images/math/9/7/1/971cd6d72286950f7f1c395617e91da2.png)

![\sigma_{x} \equiv \left( var \left[ x \right] \right)^{1/2}](/W/images/math/b/8/3/b83e9f7766f17d09d9126f073737b8ee.png)

![\sigma^{2}_{x} = var \left[ x \right]](/W/images/math/b/2/6/b269ac8c4d359055eded6a221674aa89.png)

![\left\langle \left( x' \right)^{m} \right\rangle = \left\langle \left( x-X \right)^{m} \right\rangle = \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum^{N}_{n=1} \left[x_{n} - X \right]^{m}](/W/images/math/a/0/3/a03c1958dc6ca7749232327c723e9fa5.png)